This week I celebrate the published release of my daughter Katie’s first young adult novel, The Boy Next Door. What joyous affirmation of a writer’s work, to be published! I am reminded of the confident and comforting words of poet Wallace Stevens: After the final no there comes a yes, and on that yes the future world depends. I am reminded of one of my favorite scenes from the film Back to the Future when Marty McFly’s dad reverently opens the box that contains copies of his newly released novel.

“Because for some of us, books are as important as almost anything else on earth,” says Anne Lamott in Bird by Bird (p. 15). “What a miracle it is that out of these small, flat, rigid squares of paper unfolds world after world after world, worlds that sing to you, comfort and quiet or excite you.” “I cannot remember a time when I was not in love with them,” says Eudora Welty in One Writer’s Beginnings (p. 5), “with the books themselves, cover and binding and the paper they were printed on, with their smell and their weight and with their possession in my arms, captured and carried off to myself.” A writer pours her heart and mind into the intense work of creating stories, she breathes life into words, opens a window and calls out with wonder to the world: Come join me. And one day she opens a box filled with copies of her very own book, the exhilarating confirmation that her words are going out into the world. Katie wonderfully captures that joy through photos in her blog of January 6th as she sees her novel on a local bookstore’s shelf for the first time. Congratulations and much love, Katie!  Whenever I think of the power of childhood memories, I am reminded of the MFA graduate lecture of author Sarah Sullivan while we were classmates at Vermont College. Sarah guided us in an exercise that asked us to remember a place where as a child we felt safe, a place where we felt “cradled in security.” She helped us through a series of guided questions to remember that place and suggested that in some ways we're always longing to go back. We began by drawing the place, sketching in details as best we could remember. Once immersed emotionally and visually in our “safe place”, we were asked to gradually ponder these questions: “What do you see? What do you hear? What do you smell? Are there people around you? Is there an animal nearby? What is above you? (a ceiling? tree branches? the sky?) What is below you? (water? grass? a floor?) What do you remember?” “Without our memories, what are we?” asks Leonard Pitts in a recent column. “We are the equation after the blackboard has been wiped, the sandcastle after the wave—smeared images and shapeless shapes melting into the sand.” (Chicago Tribune, p. 18, 10/30/14) He's referring to recent visits with a favorite aunt who's now living through the lens of Alzheimer’s. Yet she still remembers. Maybe not what happened ten minutes ago, but what happened fifty years ago. She remembers how to sing “The Way You Do the Things You Do” with the Temptations and how to hug her nephew, and what it feels like to go to the movies. Leonard Pitts’ fond remembrances of his aunt echo the emotional resonance of the novel The Madonnas of Leningrad by Debra Dean, a story that shows how the mundane present existence of an Alzheimer’s patient can’t hold a candle to her powerfully moving memories of life decades earlier when she helped rescue art treasures during the Nazi invasion of her hometown in Leningrad. Without our memories, what are we? Maybe the old adage, write what you know, would be better phrased, write what you remember, write what you feel. Sarah Sullivan’s memory exercises are powerful methods to get at what matters most in a story, what Sarah calls “the emotional truth, the stirrings of a writer’s heart, the wood smoke rising between the lines.” Back from a rejuvenating trip to Italy, I’ve been pondering some books I’ve read and thoughts that find connections over and over in the process of writing. Be still in moments of grace. Observe. Draw, dance, wonder. Embrace love. Hold my hand. Ti amo. “When I was very young, my mother took me for walks in Humboldt Park, along the edge of the Prairie River. I have vague memories, like impressions on glass plates, of an old boathouse, a circular band shell, an arched stone bridge. The narrows of the river emptied into a wide lagoon and I saw upon its surface a singular miracle. A long curving neck rose from a dress of white plumage. Swan, my mother said… The word alone hardly attested to its magnificence nor conveyed the emotion it produced. The sight of it generated an urge I had no words for, a desire to speak of the swan, to say something of its whiteness, the explosive nature of its movement, and the slow beating of its wings… I struggled to find words to describe my own sense of it. Swan, I repeated, not entirely satisfied, and I felt a twinge, a curious yearning, imperceptible to passerby, my mother, the trees, or the clouds.” Patti Smith, excerpts from Just Kids, p. 3 “Isn’t this what we’re really looking for? A quiet corner of light, a warm chair to hold us, the chance to adventure deeply into someone else’s world and mind through the secrets they’ve committed to the page?...I pick up a book and something in me is hushed, as something else is brought to a new alertness.” Pico Iyer,The University of Portland Magazine, Summer 2014, p. 25 “I learned not to look away at the moment when I should be paying the most attention. The closer I got to the heart of a scene, to the really difficult material to write, the emotionally challenging stuff or the exchange in which the conflict is made most explicit, the more I’d look for a way out of writing it. This was out of fear, obviously, because you don’t want to run up against your limitations in craft, intelligence or heart. It’s much easier to duck the really vital material, but it kills what you’re writing to do so, kills it instantly.” Matthew Thomas, on writing his novel, We Are Not Ourselves, interview with John Williams, NY Times Book Review – Open Book, 9/7/14

“Soon, you’ll grasp that sentences originate and take their endless variety from within you, from your reading, your tactile memory for rhythms, your sense of the playfulness at the heart of the language, your perception of the world.” Verlyn Klinkenborg, Several Short Sentences About Writing (p. 93). Take heart. Take courage. Take time. note: thanks to the slow mo guys for their inspiring slow-motion photography While I was at Vermont College, I learned an insightful question, for women in particular, to ask of ourselves: Who were you before you put yourself last? For many of us, finding out who we were means looking back to when we were teens, when we first began thinking we understood what set us apart from the world and that we knew how we would live our lives. We didn’t know, of course, but oh, the confidence of thinking we did.

I am enchanted by the ending of one of my favorite short stories, Bullet in the Brain by Tobias Wolff, when Anders, the main character, remembers how he once was “strangely roused, elated, by” the “pure unexpectedness” and “music” of words. When we who are writers finally stake our claim upon words, how deeply satisfying it is to remember back when they first charmed us. I am also mesmerized by a passage from This Boy’s Life – A Memoir by Tobias Wolff, when he describes being a troubled young man at a tailor’s shop, outfitted in a black cashmere overcoat with a claret silk scarf, looking in a mirror: The elegant stranger in the glass regarded me with a doubtful, almost haunted expression. Now that he had been called into existence, he seemed to be looking for some sign of what lay in store for him. He studied me as if I held the answer. Luckily for him, he was no judge of men. If he had seen the fissures in my character he might have known what he was in for. He might have known that he was headed for all kinds of trouble, and knowing this, he might have lost heart before the game even got started. But he saw nothing to alarm him. He took a step forward, stuck his hands in his pockets, threw back his shoulders and cocked his head. There was a dash of swagger in his pose, something of the stage cavalier, but his smile was friendly and hopeful. (p. 275-6) We do not know what lays in store for us, but there is joy in knowing that a writer’s career never ends – a writer can be published for as long as he or she can compose words. And it doesn’t matter if what was written the day before was dribble. Every day is a fresh opportunity, a clean slate to claim who we are. Our jazz world has lost another great musician. Charlie Haden, exquisite bass player, died Friday, July 11. In his July 15th tribute in the Chicago Tribune, Howard Reich, writes of how Haden suffered as a child from bulbar polio, which afflicts the throat, and says, "In a way, the bass became a kind of substitute for his voice. Perhaps that explains the ardently melodic quality of all of his playing, even in the most innovative, avant-garde settings." If you like the following sample, I highly recommend you purchase the albums Steal Away with Hank Jones or Haunted Heart with Quartet West. If you'd like to read more outstanding columns on jazz, see the link to Mr. Reich's name above.  “Time is all we’re given in this life, the hours and what we do with them. It sounds simple, but it’s true, and it makes you realize that you have to pick the areas in your life that cause time to stop, that make you feel the fullness of the moment. Art can do that.” Film director Richard Linklater, from an interview in the Chicago Tribune, July 14, 2014 This photo looks down my street towards my hometown library on a foggy night. I'm lucky every once in a while to capture a moment in a photograph that I don't know how to express in words. Except for my home page, most of the photographs on my website are ones I've taken. Books, photographs, music, drawings, paintings, sculptures, dancing...what would we do without art?

When I was a child, I loved to climb trees. Trees gave me a sense of physical exhilaration as I scaled the trunk and limbs, a far-reaching view of my patch of the world, and the healing grace of respite and solitude. Today, when I peer into the high branches of a tree, I remember the utter feeling of powerlessness I experienced as a child and the certainty each time I shimmied up a tree that I would one day emerge from the dark days into a canopy of light.  My car looks tiny parked next to the catalpa tree at the library where I work (and play) in youth services.  Five favorite picture books about trees:

A Tree is Nice by Janice Udry Leaves by David Ezra Stein Caps for Sale by Esphyr Slobodkina Christmas Farm by Mary Lyn Ray Tap the Magic Tree by Christie Matheson  A TREE GROWS IN MY HEART

Many years ago, my husband and I toured a house we hoped to buy in our local historic district. Our first concern was not the amount of restoration the house required but the massive tree out front, a towering maple with limbs resembling a sumo wrestler. The tree had grown so close to the end of the driveway, I was certain I’d hit it whenever I pulled out with our car. “You’ll never hit that tree,” my friend Sandy said. “It’s so huge you’ll always be worried when you back out, and therefore you’ll never hit it.” She was right. Though trepidation guided the first times Duane and I eased out of the driveway, the old house charmed us. We became its proud new owners and grew accustomed to maneuvering our driveway, though visitors avoided anxiety by parking on the street. Years passed with substantive house restoration. Our house became a home. In pleasant weather, we enjoyed lunches and suppers on the front porch, greeting neighbors as they passed by. I adored our maple tree for its wide arms that shaded our front lawn each summer, for its glorious shades of yellow leaves in autumn, sunlit against the sky before they cascaded down, and for the artistry of its dark branches that laced the winter clouds. Then one summer, a storm blew through town and tore one of the muscled limbs from our tree. The giant limb fell along the curb strip, its long branches extending into the street. Traffic stopped to survey the wreckage. Neighbors and passersby helped my husband and father-in-law clean up the damage. Though our front curb was no longer shaded, the tree survived and managed to shade the rest of our lawn. Years passed. More branches and limbs fell during storms, but the tree persevered. Because it grew along the curb, the city was responsible for trimming its broken branches. One year, the clean-up crew told me they should take down the tree. “Do you have to?” I pleaded. “Well, maybe not yet,” they relented. More years passed. More limbs and branches fell, and more pleading and relenting reprieved the tree. Finally one spring, only a few leaves grew in, long after the other trees on our block had turned green. Duane and I surveyed the bare branches in mid-summer and knew we had to let our tree go. The crew came and cut down the remaining branches until only the trunk remained and two limbs sticking up in the air as if the tree had surrendered. I thought my heart would break. I couldn’t watch the final removal of the trunk and roots, but in later weeks as I mourned the empty hole on our front curb and gaping space in the sky, I knew we should plant another tree as soon as possible. I called our city parks manager. “I’m getting a shipment of red maples,” he said. “Would you like one?” The crew came to plant our new tree one bright autumn day. I ran outside with a plate of cookies, bubbling with questions about care and maintenance as they planted the six-foot tree a few feet from the end of our driveway. I touched its slim silvery trunk and realized how many years it’d take before the tree would grow tall enough to shade our lawn. But its spritely branches claimed my heart, simply with its promise that it would grow. Our beautiful new maple grew several inches those first few months, and that spring, I found myself looking not at the wide space in the sky once filled with leaves and limbs but straight ahead at the branches blossoming in front of me. May the wind blow gently upon them. Suggested reading: A Tree Grows in Brooklyn by Betty Smith In my house we have one caramel colored dog and three caramel colored cats.  Sometimes our caramel colored grand-dog comes to visit.

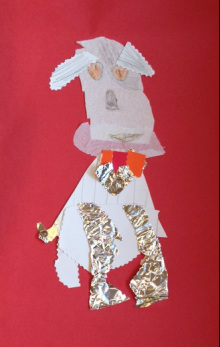

A few of my favorite dog and cat picture books: Story County Here We Come by Derek Anderson Meeow and the Big Box by Sebastien Braun Bonaparte by Marsha Wilson Chall Homer by Elisha Cooper Go, Dog, Go! By P. D. Eastman Rrralph by Lois Ehlert Here is my granddaughter’s collage homage to Ehlert’s art work: Dog Food by Saxton Freymann and Joost Elffers Widget by Lyn Rossiter McFarland The Broken Cat by Lynne Rae Perkins Skippyjon Jones by Judy Schachner There are Cats in this Book by Viviane Schwarz Mrs. Crump’s Cat by Linda Smith No Roses for Harry by Gene Zion |

Photo from Stoutcob

RSS Feed

RSS Feed